GALVANIZED YANKEE FROM FLORIDA

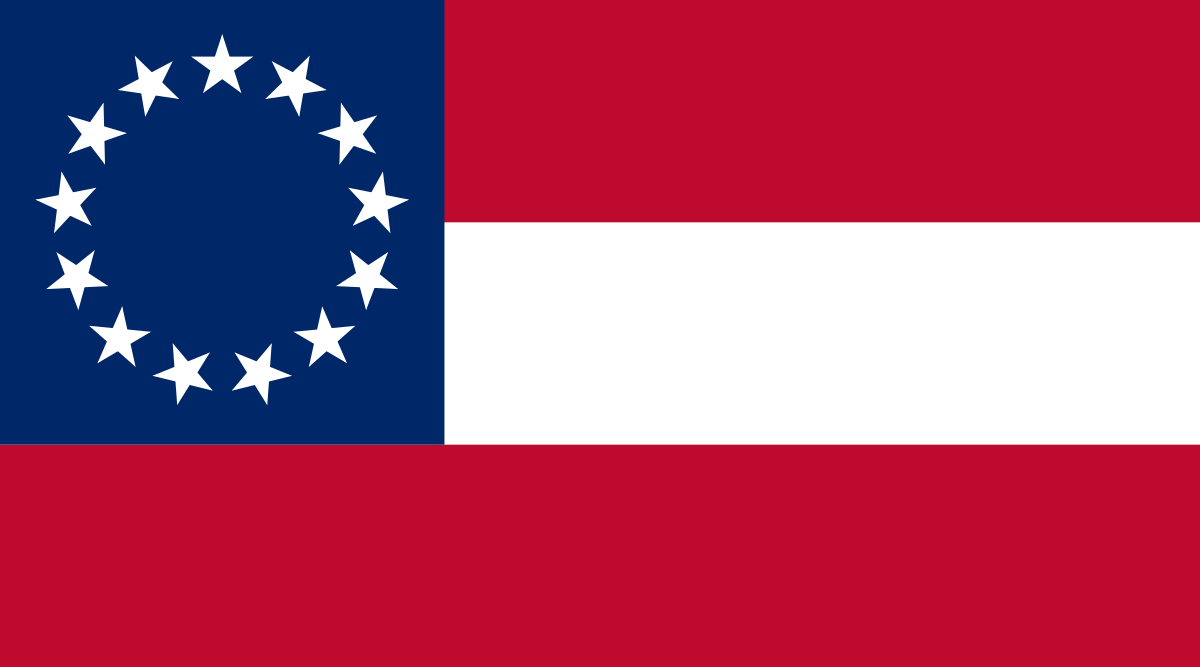

Galvanized Yankee was a derogatory Southern term used after the Civil War. It referred to a Confederate soldier who had been captured then went over to the Union side to escape imprisonment or other punishment from the Confederacy.

By Calvin Rellim March 7, 1918

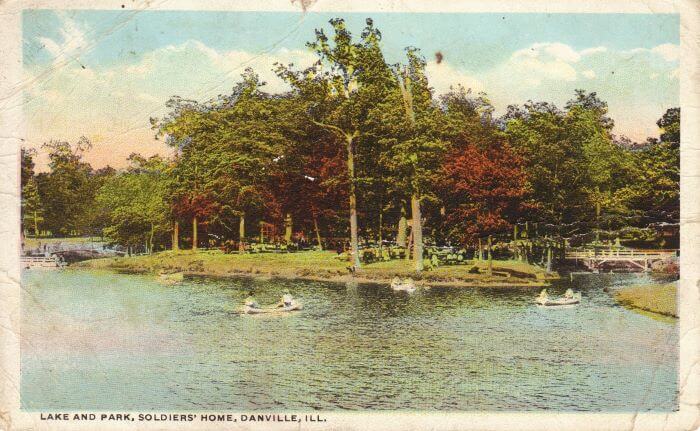

I sure never figured I’d end up here in the Old Soldiers Home with a bunch of Yankees, getting sicker and older by the day.

I’m almost 80 now, gone blind and can’t read or write anymore but my nurse, Miss Jeannette, has encouraged me to tell the story of my life.

She’s writing it down for me and fixing up my words. She feels sorry for soldiers, old and young alike.

It's 1918, and it looks like I’ll die before Miss Jeannette’s younger brother sails to Germany soon to fight old Kaiser Wilhelm and his army.

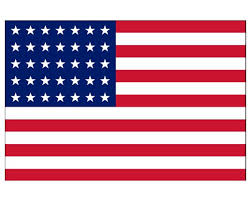

The federal government gives me free room and board here in this Yankee Old Soldiers Home because I fought for the Union Army in the Civil War.

But I don’t get a pension because I started out the Civil War fighting as a Confederate soldier.

Fighting for two countries in the same war made my life complicated and sad. It made me a “Galvanized Yankee”. I’ll explain what that means later on in my story.

I was born near Madison, Florida in 1839. My great grandfather fought for the United States in the Revolutionary War and after the war he was given a land grant near Waycross, Georgia.

I’m told it was more than 600 acres, but by the time that land got passed down and divided among his children and grandchildren there wasn’t much left for my daddy so he and Grandpa moved to Florida territory in 1830 and homesteaded 160 acres in Madison County.

I worked on the family farm from the earliest I remember and had some schooling in the one room school house down the road from our farm. That school took me through the sixth grade and that’s as far as I went.

We raised mostly corn and sweet potatoes and had some chickens, pigs, and cows. The hard work of plowing and hauling was handled by our mules. I figured on being a farmer for the rest of my life.

The biggest farmers in the county raised cotton on plantations and had plenty of slaves to pick the cotton. We didn’t have slaves and as far as we were concerned, we didn’t live any better than the slaves we knew.

Since they were the owned property of the rich farmers and planters, they got plenty of food and when they were sick they got taken care of by their owner. We were on our own regarding those things, but at least we didn’t get whipped by an overseer.

The rich planters could afford slaves all right, and they could afford to send their children to high school in Madison or hire a teacher to come live with them.

Many of them sent their children to college in Georgia or South Carolina. Since they didn’t pay the slaves any wages they had plenty of money left over for the luxuries of life. They looked down on us poor farmers.

I can’t even remember how the War Between the States got started, but we knew that a bunch of the southern states had left the Union and that the Federal Government was plumb mad about it.

Florida left the Union in 1861. I had already been married to Mary Ann for 3 years by then and we had two children, Henry and Clara.

The rich educated folks in our part of the country said we were about to have a war with the North. They said it was the Second American Revolution and another War of Independence.

After the shooting started in South Carolina, they called it the War of Northern Aggression.

I didn’t care too much about the politics of this situation. I didn’t own slaves and didn’t have a dog in that fight or so I said. But before I knew it, I got drafted into the Confederate Army and had no choice but to go off to war.

I sure didn’t want to go, but saw to it that my parents, wife, and children moved onto Grandpa’s farm where they would all have to shift for themselves while I was gone.

After training was over, I was assigned to an infantry unit and fought in a lot of little skirmishes in North Carolina and two big battles in Virginia. My unit finally ended up at Gettysburg and the Union Army beat us up pretty bad.

I was captured by the Yankees and shipped off to a prisoner of war camp in Point Lookout, Maryland.

To tell you the truth, I was relieved to get out of the fighting and began to believe I just might survive long enough to get back to Florida.

But life in the Yankee prison camp turned out to be just as bad as the battlefield. We never had enough to eat, and when we did get food it was usually rotten and crawling with maggots. The Yankee soldiers still fighting in the war were getting the good rations.

When we got sick, we had to get well on our own because there were no doctors and no medicine. My comrades were dying like flies and those of us still alive were too weak to escape.

We were finally given a chance to get out of the prison camp. We could swear allegiance to the Federal Government and become soldiers in the Union Army.

Not many prisoners took up that offer, but I figured I didn’t start this war anyway and I wanted to get home alive and it looked pretty certain after Gettysburg that the South was going to lose the war. I figured I might as well be on the winning side.

So I volunteered for the U.S. Army and got out of camp and was sent off for training in Kansas.

Union General U.S. Grant did not want former Confederates fighting against the Confederate Army, so he decided we would be more useful fighting Indians out west.

So that’s how I became a Union soldier and Indian fighter.

It wasn’t long before I began to wish I’d stayed in prison camp.

My unit got shipped out to Colorado and we started fighting the Sioux and Cheyenne Indians. It was awful. The Indians didn’t believe in taking prisoners and every battle was a fight to the death.

The Indians didn’t even have a word for surrender and they were mean fighters. They could fight from a horse better than the Union cavalry I had faced. You had to hope they killed you rather than capture and torture you.

Along about this time we got transferred to Wyoming to fight more Indians. The Civil War was over but I was still obligated to fight Indians for another two years.

Shortly after the transfer I received a letter from my wife telling me she could wait for me no longer. She had divorced me and married a farmer from near Tallahassee. She said she was sorry, but it was for the welfare of the kids.

Just when I was feeling about as bad as I thought I ever could, I was jabbed hard in the left elbow by an arrow during a fight with some Indians.

The arm got infected and the surgeon had to cut if off when gangrene set in. I had never before felt such pain and hope I never do again. The only good thing was I was finished as a soldier and discharged from the army.

I wanted to go back to Florida to see my children but was not welcome. Word had gotten around Madison County that I had bailed out on my country.

I found my way to Kentucky and started working for a farmer near Louisville. I wasn’t too far from my brother who had settled in northern Kentucky after the war.

I spent my entire life working on farms in Kentucky and southern Indiana until I was too old to earn my keep. I never got married again, and have never seen my kids to this very day.

Before I knew it, I was a 70 year old one armed man with no money and no prospects. Nobody wanted me as a hired hand. I was not eligible for a Confederate pension because I had left their army to become a Union soldier.

I could not get a Union pension because I had actively fought against the Union army earlier in the Civil War. The only thing available to me was an Old Soldiers Home.

These homes were set up to take care of old Union soldiers in their final years. There was an opening at the home in Danville, Illinois, so I moved in back in 1910.

Like I told you earlier, I don’t get a pension from either the North or the South. Ever since I moved into this home, Miss Jeannette has helped me write my brother twice a year and ask for money.

He would usually send me $50, so I had to make it last me six months until she wrote the next letter. I had to send the letters because my brother wouldn’t send the money on his own.

That’s just the way he is and he didn’t approve of my leaving the Confederate army in the way I did.

I won’t be a burden to my brother much longer and that’s good because I don’t like to be a beggar. I don’t need much.

The Old Soldiers Home gives me room and board, and my brother’s money helps me buy a cigar now and then and have a sip of whiskey from time to time.

Much obliged for reading my story.

Our Facebook page has more than 130,800 followers who love off the beaten path Florida: towns, tourist attractions, maps, lodging, food, festivals, scenic road trips, day trips, history, culture, nostalgia, and more.

By Mike Miller, Copyright 2009-2025

Florida-Back-Roads-Travel.com

Florida Back Roads Travel is not affiliated with or endorsed by Backroads, a California-based tour operator which arranges and conducts travel programs throughout the world.